Finding Gold in the Glitches

Near the end of the 19th century, when electric light was still a novelty and illuminated only the homes and businesses of the very wealthy, Thomas Edison stumbled upon an interesting observation. While examining one of his incandescent lamps, he noticed something rather odd: a small black spot on the inside of the glass, always near the filament. This was not accidental. The glass was pristine when sealed, the vacuum inside prevented dust from floating around, and the filament never made contact with the bulb’s surface.

This small aberration – this unexplained dot – was so exasperating that it might have kept the great inventor awake at night.

Yet despite his unparalleled reputation for tenacity (having famously tested thousands of materials before finding a suitable filament), Edison eventually abandoned this particular mystery. “I was working on so many things at that time,” he later confessed, “that I didn’t have time to do more.” He moved on to more immediately profitable ventures, unknowingly walking away from what would become one of the most transformative discoveries in scientific history.

Enter Joseph John Thomson – “J.J.” to his friends – a man whose theoretical brilliance compensated for his notorious clumsiness in the laboratory. Where Edison excelled at practical application, Thomson thrived in abstraction. Intrigued by similar phenomena, Thomson constructed modified versions of Edison’s bulbs and manipulated whatever was emanating from the filaments using magnetic fields. His systematic study resulted in the 1897 discovery of the electron – revolutionizing our understanding of atomic structure and paving the way for modern physics.

The humble black dot that Edison dismissed? It was the impact point of electrons escaping from the filament and striking the glass – physical evidence of subatomic particles no one had yet proven existed. Edison amassed wealth. Thomson revolutionized science and won the Nobel Prize.

From Historical Anecdote to Modern Insight

This historical footnote recently grabbed my attention while I was doing some research on innovation patterns. The contrast was striking – two brilliant minds (Edison and Thomson) encountered the same anomaly, but only one recognized its significance. The story’s implications for how we approach unexpected findings stuck with me, eventually inspiring me to create a short video titled “The Dot That Could Have Changed Everything.”

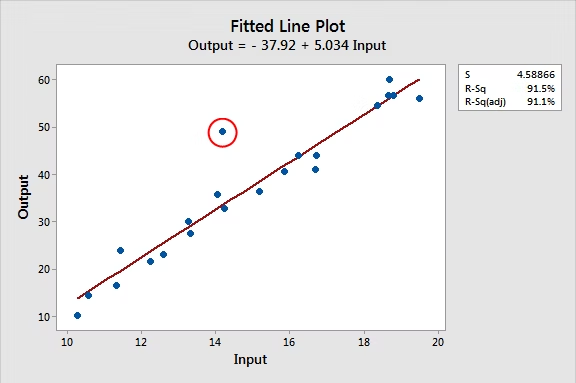

The video, while brief by design, only allowed me to scratch the surface of the powerful parallel between Edison’s missed opportunity and today’s data analytics challenges. Near the end of my video, I condensed the central insight into two sentences: “Sometimes, the insight that changes everything isn’t in the trend; it’s in the anomaly. So, when something doesn’t add up, don’t just scroll past it; dig deeper. It might just be your electron moment.”

But this concept deserves deeper exploration than a 90-second or so snapshot can provide. After reflecting on the video’s message and drawing from three decades of experience in data analytics, I felt compelled to expand these ideas into this article – to examine how the principles illustrated by the Edison-Thomson story apply across modern analytics practices and organizational decision-making.

Deviation Thinking: The Power of Investigating What Doesn’t Fit

The Edison-Thomson dichotomy is a great example of what I’ve begun referring to as “Deviation Thinking” – the conscious practice of paying particular attention to data points that don’t line up with our expectations.

In the world of data analytics, there are many examples of revolutionary discovery that resulted not from examining common patterns but from investigating anomalies. Consider the development of pulse oximetry technology, now standard in medical care worldwide. Engineers at Hewlett-Packard in the 1970s were testing early prototypes when they noticed unexplained fluctuations in their readings – noise that most researchers would have filtered out or recalibrated away. Instead, they investigated further and discovered these “errors” corresponded precisely with arterial pulse waves. This unexpected finding led directly to the development of technology that now saves millions of lives annually.

In the world of data analytics, there are many examples of revolutionary discovery that resulted not from examining common patterns but from investigating anomalies. Consider the development of pulse oximetry technology, now standard in medical care worldwide. Engineers at Hewlett-Packard in the 1970s were testing early prototypes when they noticed unexplained fluctuations in their readings – noise that most researchers would have filtered out or recalibrated away. Instead, they investigated further and discovered these “errors” corresponded precisely with arterial pulse waves. This unexpected finding led directly to the development of technology that now saves millions of lives annually.

Or consider how weather prediction models improved dramatically after meteorologists began examining forecast failures rather than successes. By studying the conditions under which their models performed poorly – the anomalous results – they identified critical variables previously overlooked. Each model failure, properly analyzed, strengthened future predictions.

The field of cybersecurity essentially revolves around Deviation Thinking – detecting patterns that diverge from normal network behavior often provides the earliest warning of security breaches. Companies that excel at threat detection don’t just monitor for known attack signatures; they actively investigate behavior that deviates from established baselines.

Even in product development, many breakthrough innovations emerged from investigating unexpected user behaviors. The creators of Post-it Notes famously discovered their product by investigating a “failed” adhesive – one that stuck too weakly for its intended purpose but perfectly for temporary notes. The anomaly wasn’t a failure; it was an opportunity viewed through the wrong lens.

In each case, the breakthrough didn’t come from analyzing normal patterns. It came from investigating deviations from those patterns.

Edison was focused on making the bulb work better. Thomson was curious about why it worked at all – including why it sometimes left mysterious marks. The difference in those approaches led to profoundly different outcomes.

Edison was focused on making the bulb work better. Thomson was curious about why it worked at all – including why it sometimes left mysterious marks. The difference in those approaches led to profoundly different outcomes.

Deep Drilling: When Something Doesn’t Add Up, Don’t Scroll Past

The complementary practice to Deviation Thinking is what I call “Deep Drilling” – the disciplined pursuit of explanation when confronted with unexpected data. This requires both technical capability and intellectual courage.

Take the notorious case of the “Breathalyzer Bug” uncovered in 2019. That year, a huge scandal erupted over the reliability of breathalyzer machines used in DUI cases. Defense attorneys and legal experts had complained for years about inconsistent breath test results, typically blamed on calibration issues or procedural mistakes. But an extensive investigation by journalists and attorneys uncovered systemic flaws in the software and maintenance of the devices.

The findings were staggering. Thousands of breath tests in Massachusetts and New Jersey were invalidated due to faulty calibration, expired chemical samples, and even computer bugs. These revelations led to the dismissal of numerous DUI cases and sparked widespread judicial reviews on a massive scale. What began as sporadic anomalies ultimately exposed a national issue, questioning the admissibility of breathalyzer evidence in courts across the country.

The barrier to this “Deep Drilling” concept isn’t usually technical capability – it’s psychological resistance. We develop cognitive shortcuts that help us process information efficiently but can blind us to the significance of anomalies. We rationalize unexpected findings rather than investigating them. We dismiss outliers to make our models cleaner rather than viewing them as potential sources of insight.

Over my three decades in the field of data, I’ve observed a consistent pattern: organizations that institutionalize “Deep Drilling” practices significantly outperform those that prioritize the rapid processing of data. The former may move more slowly initially, but they discover insights their competitors miss entirely.

Implementing the Anomaly Advantage

To cultivate these Deviation Thinking and Deep Drilling practices within your organization:

- Create systematic anomaly identification protocols. Don’t rely on chance observation – build processes that deliberately flag deviations from expected patterns and bring them to analysts’ attention.

- Allocate “exploration time” specifically for investigating unexplained phenomena. Edison’s greatest regret was letting time pressure push him past the mysterious dot. Don’t make the same mistake.

- Reward anomaly investigation, not just problem resolution. Create incentives for team members who thoroughly investigate unexpected findings, even when they don’t immediately lead to actionable insights.

- Document and share unexplained observations. Thomson built on Edison’s initial observation years later. Your unexplained anomaly might be another team’s breakthrough insight.

- Cultivate intellectual humility. The phrase “that’s just noise in the data” often masks our inability to explain something important. Train analysts to recognize when they’re dismissing observations they can’t explain.

The Electron Moments Awaiting Discovery

As we navigate an increasingly data-saturated business environment, the competitive advantage will increasingly come not from having more data, but from developing better practices for identifying and investigating the unexpected within that data.

developing better practices for identifying and investigating the unexpected within that data.

As Albert Einstein once remarked, “The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.” This sentiment captures the essence of what I’m advocating; that is, a systematic approach to maintaining curiosity about what doesn’t fit our models and expectations.

“The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.”

(Albert Einstein)

Edison became wealthy by perfecting what was already understood. Thomson changed history by investigating what was NOT understood. In your own data practices, which path will you choose?

The next time you encounter an unexplained pattern in your data – your own version of that puzzling black dot on the bulb – remember: it’s not just an inconvenient anomaly disrupting your analysis. It might be your electron moment waiting to be discovered.

inconvenient anomaly disrupting your analysis. It might be your electron moment waiting to be discovered.

And in that moment, the choice you make could determine whether you merely succeed at what’s already known or transform what’s possible in your field. The most valuable insights often aren’t found in the trends that everyone sees – they’re hiding in the anomalies that most people ignore.

“The most valuable insights often aren’t found in the trends that everyone sees – they’re hiding in the anomalies that most people ignore.” (Dr. Joe Perez)

The question isn’t whether these anomalies exist in your data. They DO. The question is whether you’ll have the wisdom to notice them and the courage to investigate where they lead.

The choice is yours. Will you be Edison, or will you be Thomson?

- by

- by